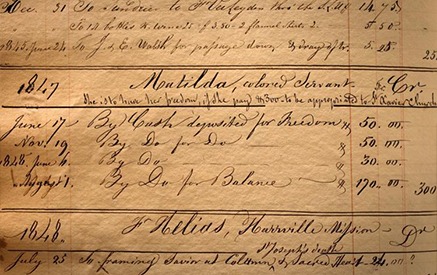

An entry in 1847 in an original ledger from Missouri Jesuits shows a “colored servant” named Matilda could buy her freedom for the price of $300 − “to be appropriated to” St. Francis Xavier Church. The record was photographed on Wednesday, Sept. 2, 2020, at the Jesuit Archives and Research Center. Photo by Christian Gooden, cgooden@post-dispatch.com

ST. LOUIS — In 2019, the Jesuits, a Roman Catholic religious order that has guided St. Louis University since its founding, reached out to descendants of people they enslaved in the region between 1823 and 1865.

Robin Proudie, was one of them.

She says early efforts to reconcile and hear descendant voices have since fallen away. On Thursday, trying to reinvigorate dialogue, she, extended family and supporters held a press conference and “teach-in” event in the heart of the private university.

About 75 people attended. Few of them were college students.

“Our ancestors deserve to be taken from the darkness and brought to light on this campus,” Proudie, 58, told the crowd gathered at a Busch Student Center banquet hall. “Where are you? We want to collaborate with St. Louis University to get this work done.”

Proudie helped form the organization Descendants of the St. Louis University Enslaved.

“We are not asking for a handout,” she added. “We are asking for the debt to be paid.”

A local partnership between the Jesuits and St. Louis University to research their history of slaveholding, including finding and reconciling with descendants, was quietly downsized in recent years.

The Jesuit order, which works around the globe, previously said it is still committed to the mission of the Slavery, History, Memory and Reconciliation Project, but the project has been folded into a broader effort being developed that’s more unified and eliminates overlap.

Jesuit pioneers like Pierre-Jean De Smet first brought six slaves with them in 1823 from White Marsh Plantation, in Maryland, to establish a mission in Missouri. By 1865, they had enslaved at least 74 people in the St. Louis region. They were mainly forced to work at the university, its church and St. Stanislaus Seminary, which initially operated as a farm in the Florissant area.

Proudie and about 200 of her relatives are descendants of Henrietta Mills-Chauvin. They recently retained civil rights attorney Areva Martin to represent them.

“We say justice for these families is long overdue,” Martin, a St. Louis native who lives in Los Angeles, said at the press conference. “It’s always the right time to do the right thing.”

The value of labor for 70 enslaved people in the St. Louis region ranges anywhere from $365 million to $70 billion in today’s dollars, depending on the interest rate, said Julianne Malveaux, a Washington, D.C.-based economist and former president of Bennett College. She told the crowd that her calculation was based on getting paid 5 cents an hour.

“It doesn’t account for pain and suffering,” she said.

In an interview, Martin said her clients didn’t expect the university to “disgorge” a huge check. She wants it to be “a starting point for negotiations.”

“We want the valuation of the wages to be a part of the conversations,” she said.

She said university officials weren’t at the on-campus event Thursday but agreed to meet on Friday.