Our History

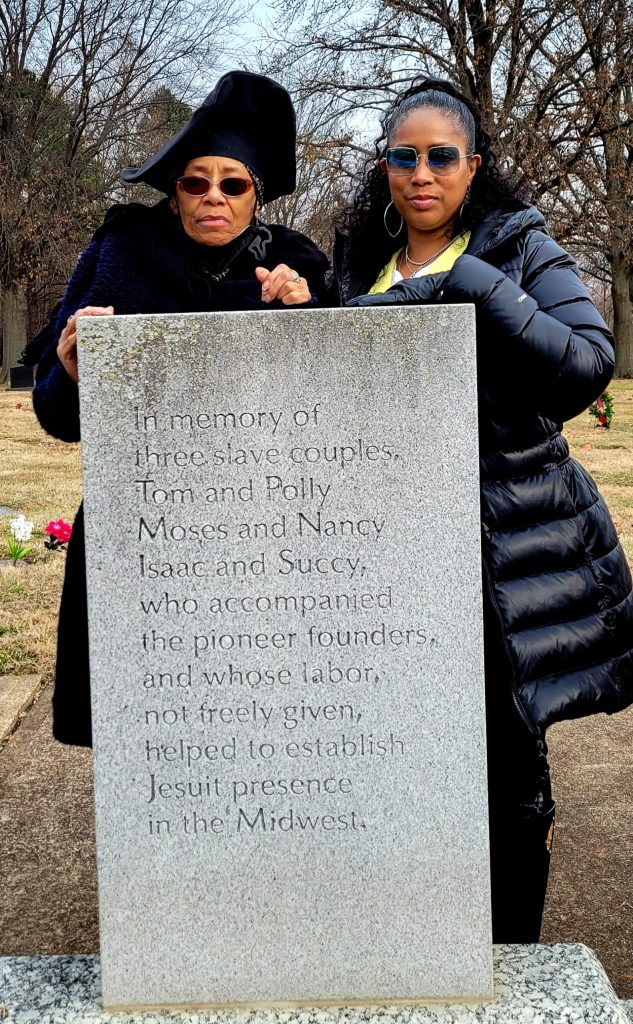

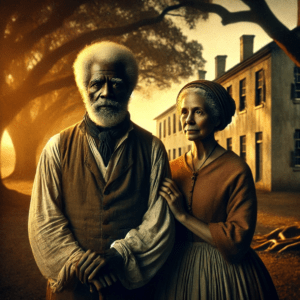

Descendants Safiyah Chauvin and Robin Proudie stand behind a small memorial located at Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri. These six couples were the first DSLUE Ancestors to be forced to migrate from the Jesuits’ White Marsh plantation in Maryland to Missouri in 1823.

Dry Bones Get Breath

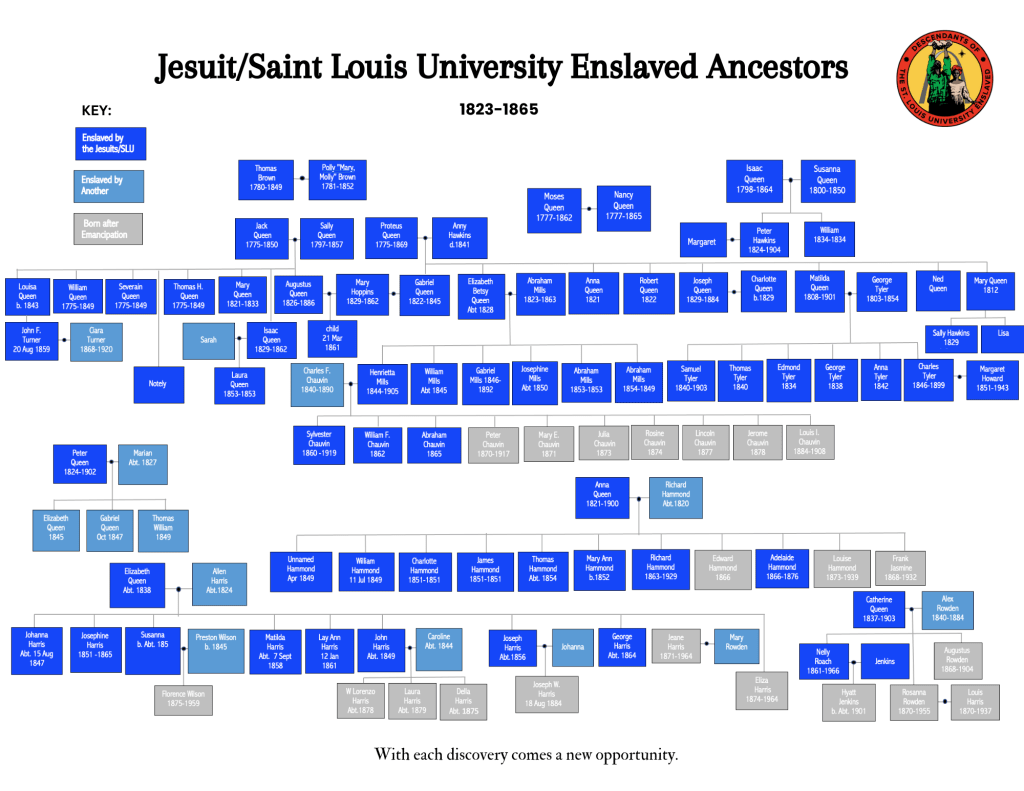

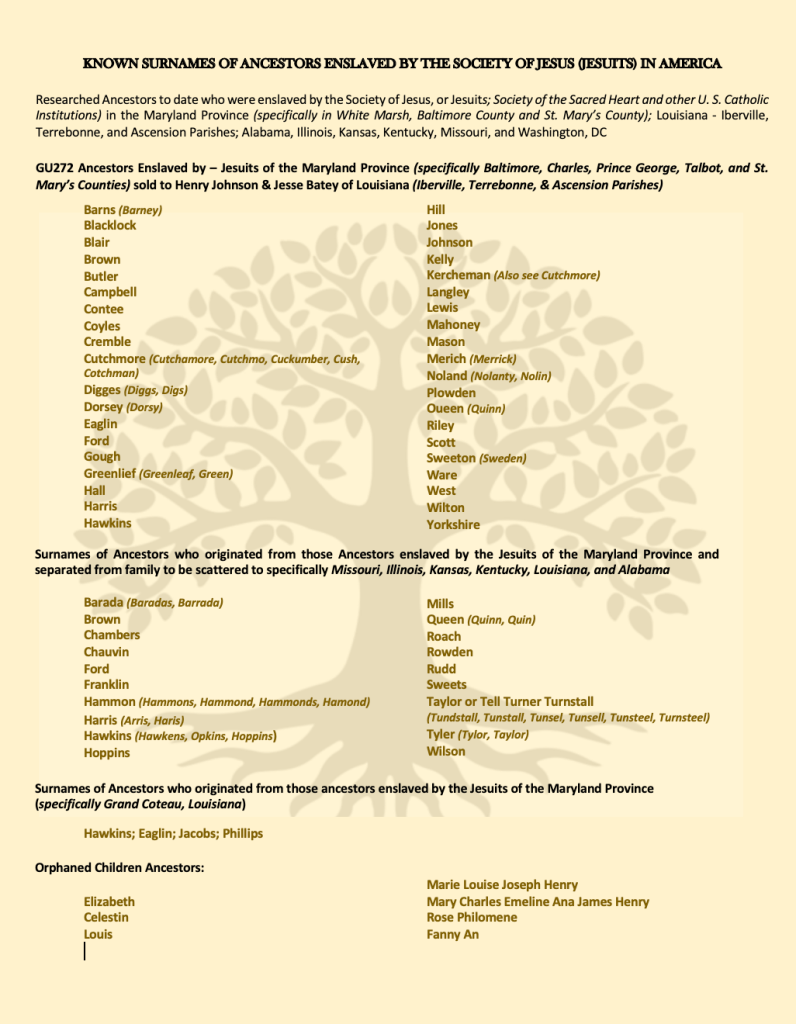

When DSLUE founder Robin Proudie first met researchers Kelly Schmidt and Ayan Ali, they shared with her original documents from the Saint Louis University Archives, Jesuit Archives & Research Center, and other archives located in St. Louis, Missouri. Documents that revealed her great grandmother, three times removed, Henrietta Mills, was born into slavery at Saint Louis University (SLU) around 1844. Fascinated by what she had learned, Robin combed through the many documents the research team had compiled, transcribed, and translated during the three years of work with the Slavery, History, Memory, and Reconciliation (SHMR) Project.

An initiative that studied Saint Louis University and the USA Central and Southern Province Jesuits’ ties to the institution of slavery. The research has since revealed that about 200 black human beings were trafficked by SLU and the Jesuits in Missouri, Kansas, Kentucky, Alabama and Louisiana, from 1823 to 1865. For Robin, the names on the records breathed back to life the dry bones of upwards of almost 70 of her ancestors, people, who had been used, abused, slained, and forgotten.

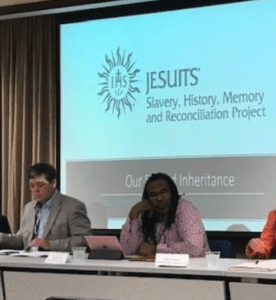

In late 2019, after being contacted by the project team researchers, descendants Safiyah Chauvin, Stephen Chauvin, Greg Holley, and Sonjia Williams began attending SHMR working group meetings at Saint Louis University. The intent was to learn about the forgotten lives of their Ancestors uncovered by the research. In March 2020, that all changed when the Covid-19 pandemic reared its deadly head and shut down the entire world. In-person meetings stopped as virtual meeting spaces took hold. Familiar with virtual platforms, Robin stepped in the gap to continue the important work her elders started.

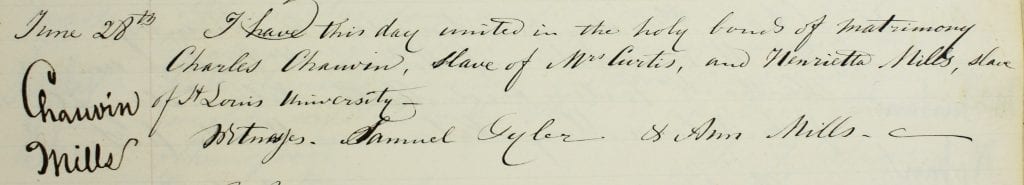

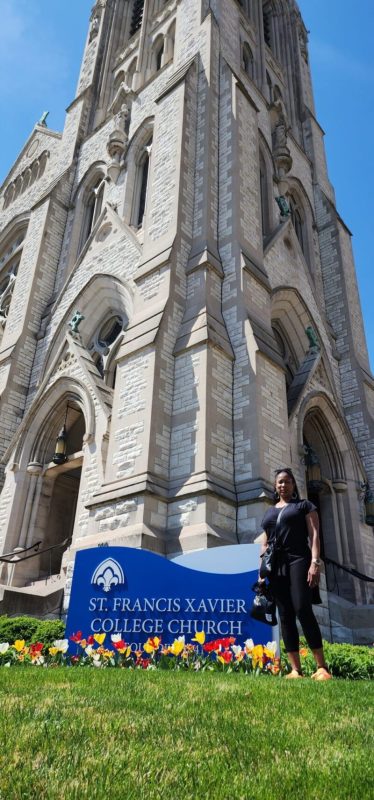

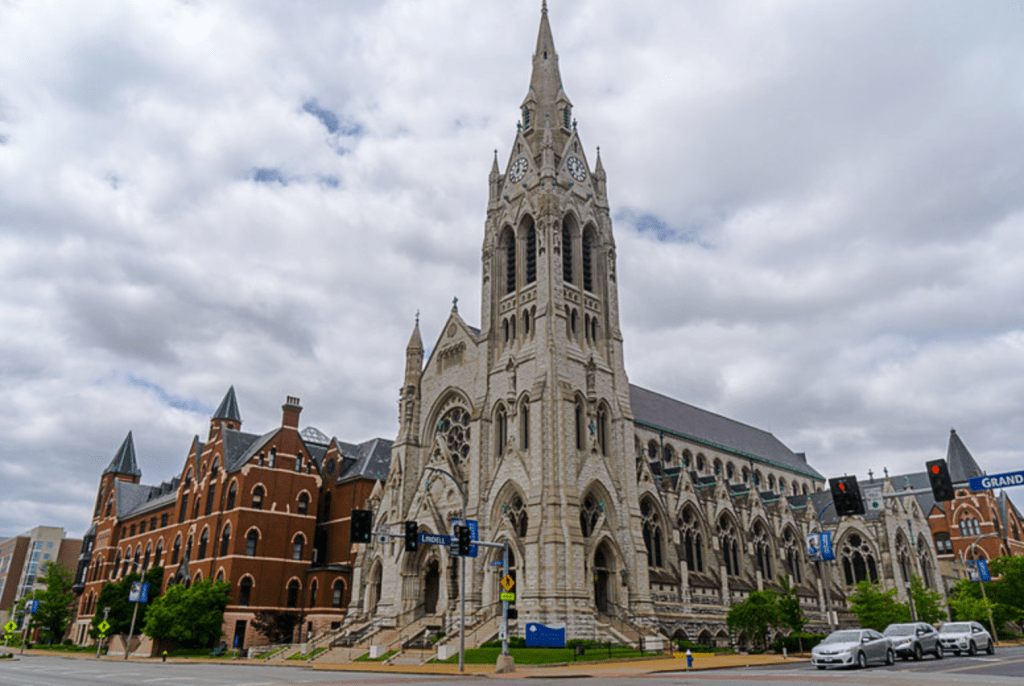

An archival record the DSLUE holds near and dear is housed at the Archdiocese of St. Louis Office of Archives and Records. It was recorded by a Jesuit priest on June 28, 1860. It reads: “I have this day united in the holy bonds of matrimony Charles Chauvin, slave of Mrs. Curtis, and Henrietta Mills, slave of St Louis University, witnesses Samuel Tyler and Ann Mills.” The marriage most likely took place in the “colored chapel” in the upper gallery at the old St. Francis Xavier College Church. Their witness, Samuel Tyler, was a cousin to Henrietta Mills, and it is believed that Ann Mills was also kin to Henrietta.

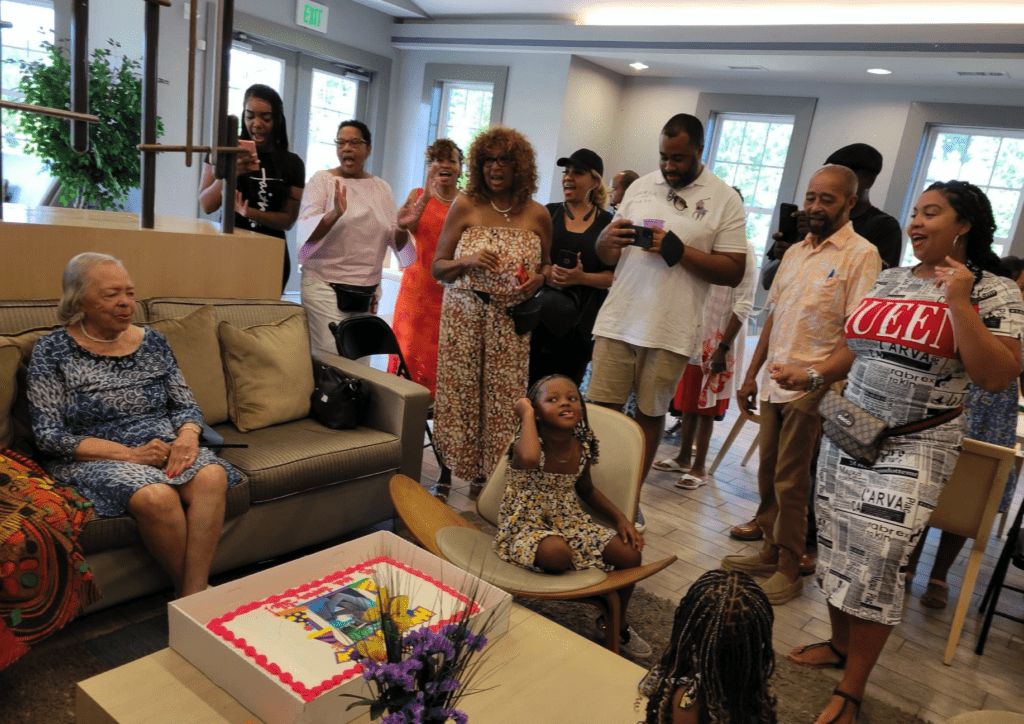

DSLUE Elders that participated in the early workshops at Saint Louis University.

June 28, 1860 record reads: “I have this day united in the holy bonds of matrimony, Charles Chauvin, Slave of Mrs. Curtis, and Henrietta Mills, Slave of St. Louis University.” Image courtesy of the Office of Archives and Records fo the Archdiocese of St. Louis.

But For Our Ancestors

It was a moving experience for descendants to read actual records that documented the marriage that endured so that they could be here today. Unions between enslaved people during this dark time in our historical past, are often romanticized in narratives put forth today. Even entanglements between the enslaver and those they enslaved are often depicted as consensual or as being a “love affair.” It’s an uncomfortable truth that enslaved people had no agency over their lives or their bodies. Instead, they were human beings treated as property, to be bought, sold, rented, psychologically and sexually abused, and bred, at the will of those who enslaved them.

Illustration of a Jesuit priest marrying Charles Chauvin and Henrietta Mills in the upper “colored” Chapel at St. Francis Xavier College Church on June 28, 1860.

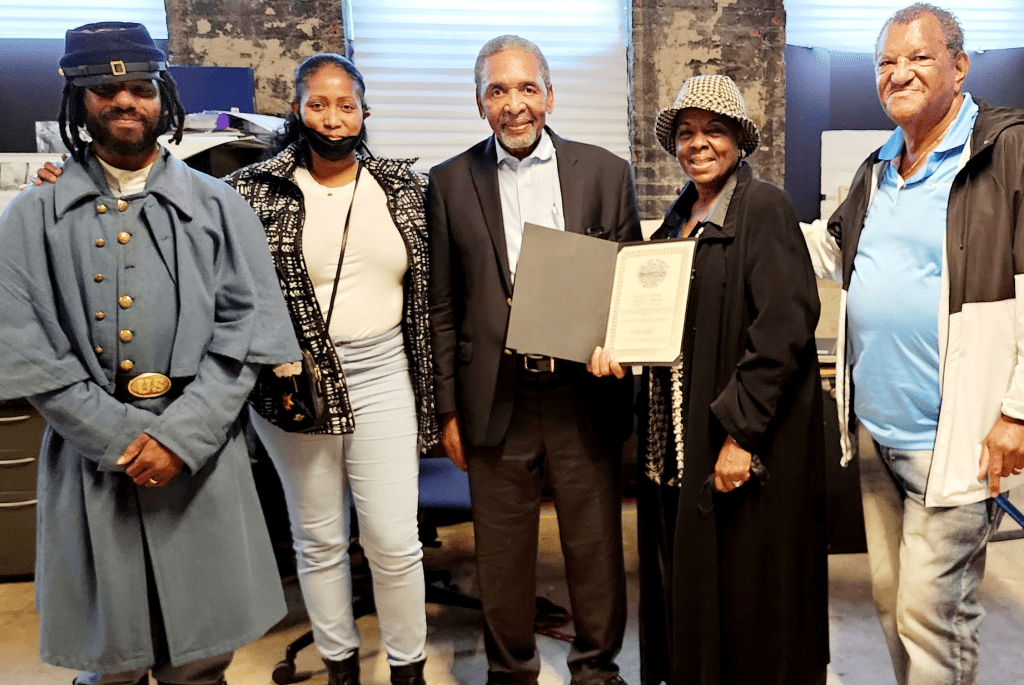

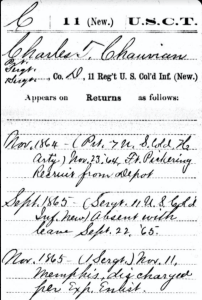

Nevertheless, the DSLUE families rejoice in the legacy of their forebearers’ perseverance. Charles’ and Henrietta’s marriage came together under the massive weight of human bondage, and endured the ravages of the American Civil War. In November of 1864, Chauvin was drafted out of bondage and into the U.S. Colored Infantry as a private in the Union Army. Fueled by the possibility of freedom for himself and his growing family, he fought gallantly and rose to the rank of sergeant. He was discharged on November 11, 1865. Charles F. Chauvin, like his grandfather-in law Proteus Queen, continued a legacy of honorable military service to this country that many of his descendants share in common today.

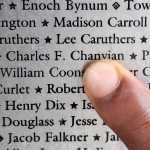

Descendants travel to Washington D.C. to honor Ancestor and hero, Charles F. Chauvin, for his service in the Civil War. They visited the African American Civil War Memorial where the founder, Frank Smith, presented DSLUE with a certificate honoring Charles for being one of the 209,000 black heroes who helped to win the Civil War and save the Union.

After the war, Charles returned to St. Louis and reunited with his wife, three children, and extended family, some blood and others tied together through the unbreakable bonds of survival forged through generations of hardship and hope. To survive after slavery’s abolition, they took jobs as laborers, porters, washers, and carpenters. They did what they could to feed their growing family. Between 1860 – 1884, Charles and Henrietta had ten children: Sylvester I (1860), William Francis (1862), Abraham (1865), Peter (1870), Mary Elizabeth (1871), Julia (1873), Rosine (1874), Lincoln (1877), Jerome Alexander (1878), and Louis Ignatius (1884). Lincoln, or “Link” Chauvin is the direct line from which the founders of DSLUE descend.

After the war, Charles returned to St. Louis and reunited with his wife, three children, and extended family, some blood and others tied together through the unbreakable bonds of survival forged through generations of hardship and hope. To survive after slavery’s abolition, they took jobs as laborers, porters, washers, and carpenters. They did what they could to feed their growing family. Between 1860 – 1884, Charles and Henrietta had ten children: Sylvester I (1860), William Francis (1862), Abraham (1865), Peter (1870), Mary Elizabeth (1871), Julia (1873), Rosine (1874), Lincoln (1877), Jerome Alexander (1878), and Louis Ignatius (1884). Lincoln, or “Link” Chauvin is the direct line from which the founders of DSLUE descend.

As young adults in the late 1800s, the Mills-Chauvin children worked in various occupations, including as mattress makers, barbers and musicians. Sylvester, Abraham, Peter, Lincoln, and Louis were all talented musicians involved in St. Louis’s popular ragtime scene.

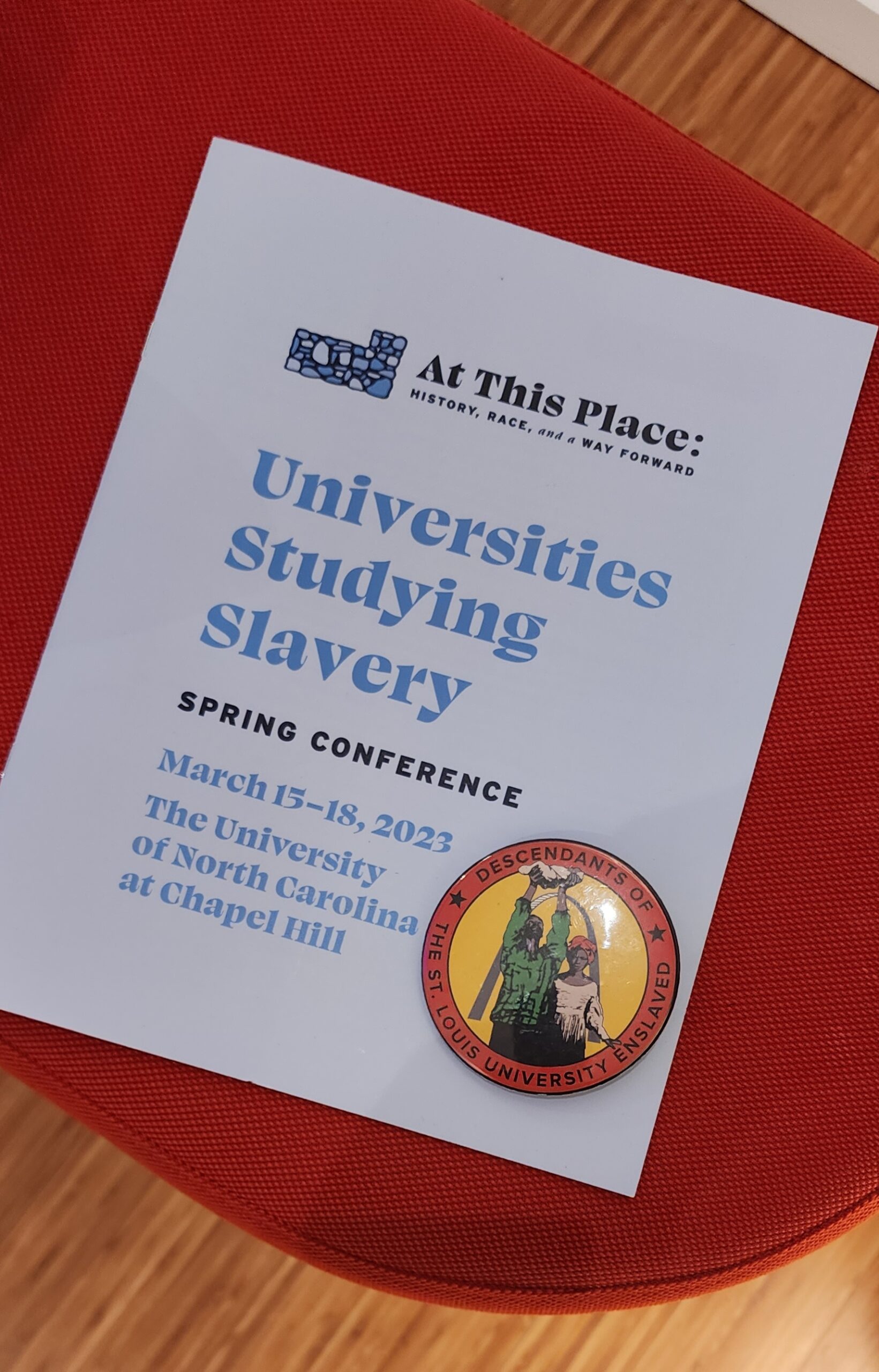

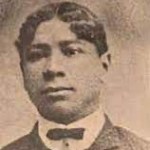

Sylvester, Abraham, and Peter played brass instruments, while his brother Lincoln “Link” Chauvin played guitar. Louis Chauvin, the youngest of the Chauvin brothers, became the most famed of the Chauvin musicians.

Louis was highly regarded as a prodigy among peers, like Tom Turpin and Sam Peterson. He performed and team up with Sam Patterson to form the Mozart Comedy Four, a quartet that sang opera songs and negro spirituals.

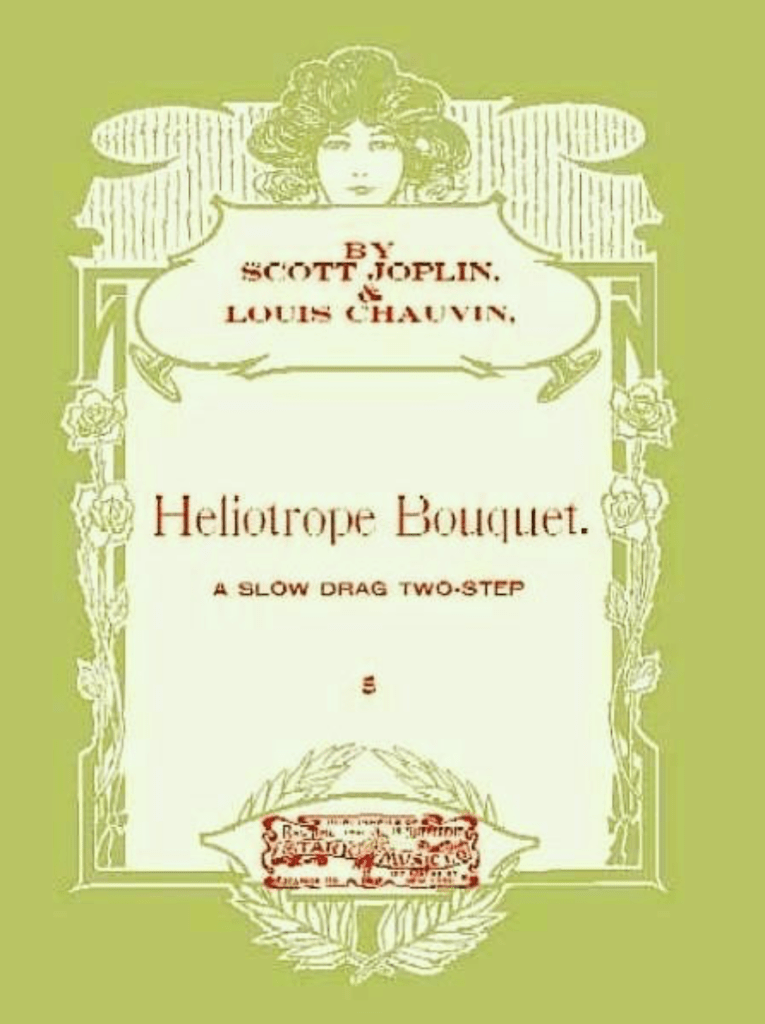

In 1904, he won a coveted medal playing piano at the St. Louis World’s Fair. Although, Louis performed many original works during his career, he had three published works: “The Moon is Shining in the Skies” with Sam Peterson (1903), “Babe, It’s Too Long Off” words by Elmer Bowman (1906), and his most popular, co-composed with Scott Joplin, “Heliotrope Bouquet” in 1907.

Ancestor Louis Chauvin’s genius was brought to life in the 1977 film, Scott Joplin by legendary actor and songwriter, Clifton Davis. The king of Ragtime, Scott Joplin, was played by Emmy nominated actor, Billy D. Williams.

DSLUE Ancestor Charles F. Chauvin’s name is listed on the wall of the African American Civil War memorial (name will be corrected).

Descendants Robin and Kay visit the African American Civil War Memorial in Washington D.C.

Record of Charles F. Chauvin’s military service in the Union Army.

DSLUE Ancestor Louis I. Chauvin, Gifted Ragtime Musician

Heliotrope Bouquet composed by Scott Joplin and Louis Chauvin

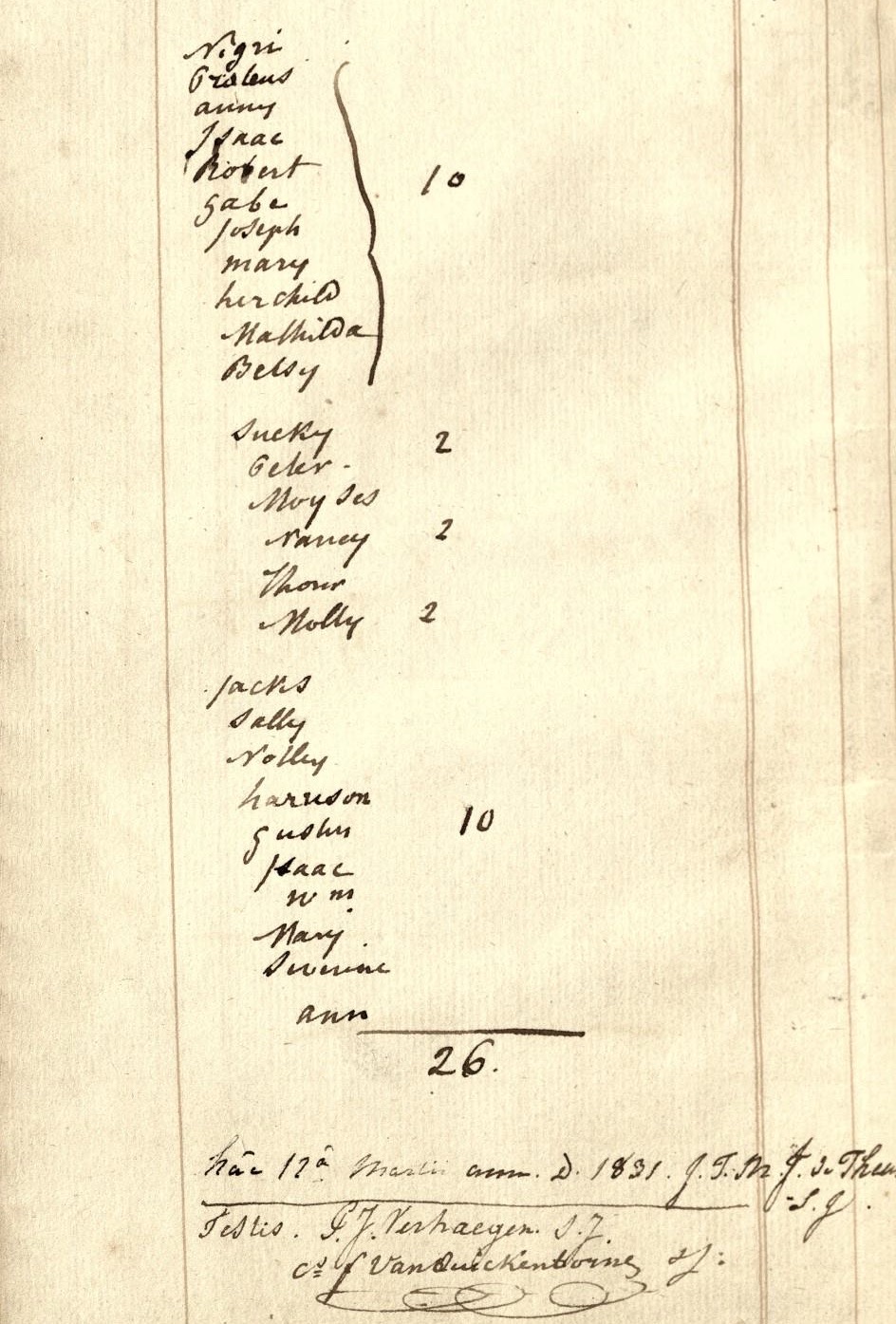

Ledger recorded in 1831 of DSLUE Ancestors who were made to labor at St. Stanislaus in that year, most of whom had been forced from the Jesuit’s White Marsh plantation in Maryland to Missouri in 1823 and 1829.

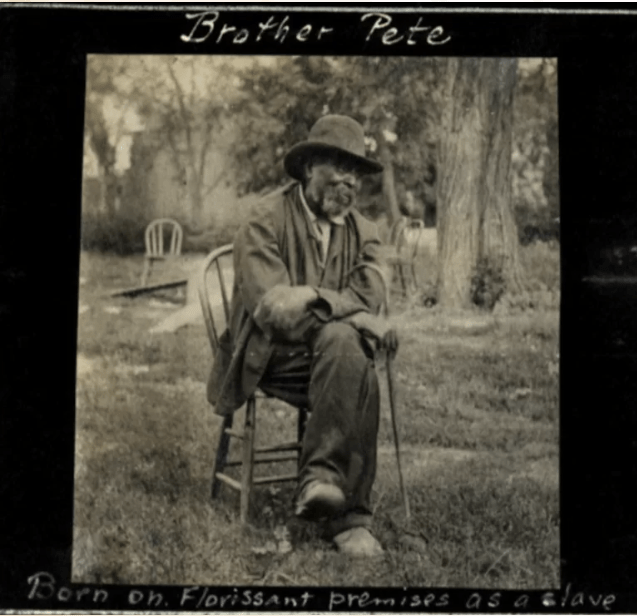

Who was Peter Hawkins?

PETER HAWKINS BORN (824-1907)

Peter Hawkins was the first child born into slavery at the Jesuits’ Saint Stanislaus Novitiate and Farm in Florissant, Missouri, and the last formerly enslaved person to leave the seminary after emancipation. He witnessed and lived through almost the entirety of enslaved people’s presence at Saint Stanislaus and. As an adult, Peter’s wisdom, and experience, led fellow enslaved and emancipated black people in the Florissant Valley area to choose him as their godfather at baptisms and as witness at their marriages.

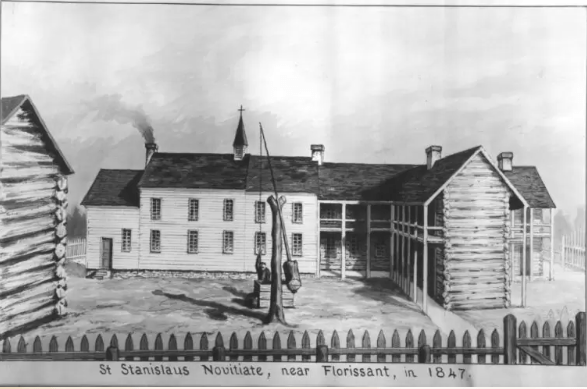

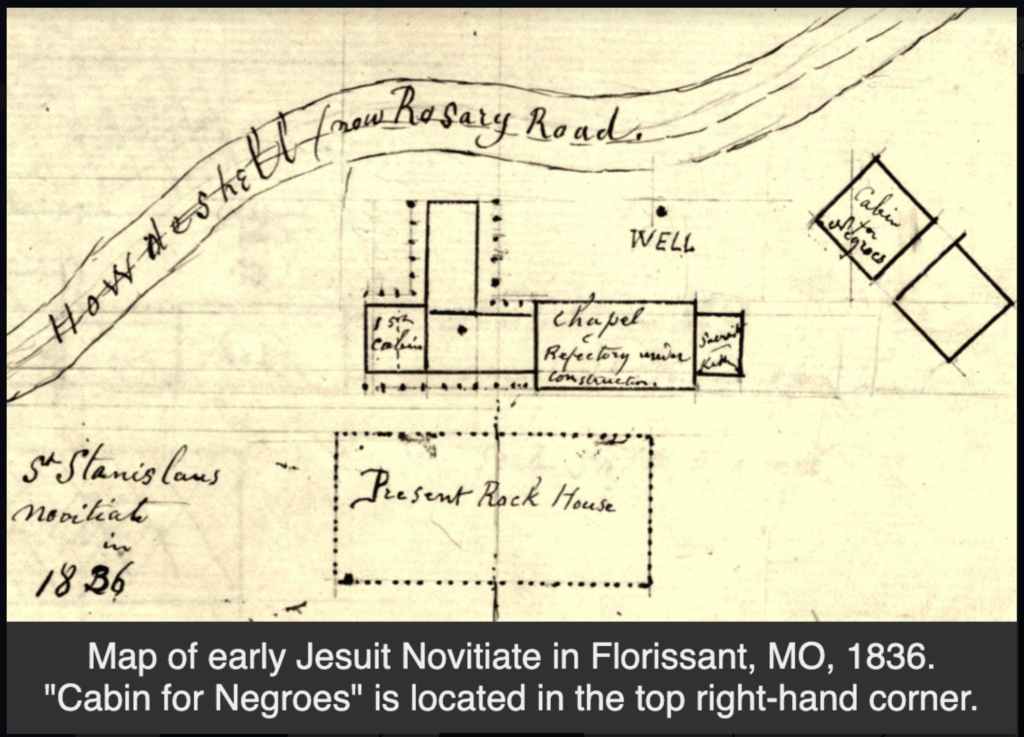

Peter’s parents, Isaac Hawkins, and Susanna (often called Susan, or Succy) Queen, were newlyweds of only four months when they were forced along with two other enslaved couples to aid in founding the Jesuits’ new Missouri mission. In May 1823, they endured a monthlong journey of over a thousand miles by foot and flatboat along the Ohio River from the Jesuits’ plantation in White Marsh, Maryland, to Florissant, Missouri. Isaac frequently navigated the flotilla out of trouble when caught in a current and steered the boats at night. After arriving in Florissant, Isaac and Susan settled into a crowded, one room log cabin that doubled as the kitchen and laundry, which they shared with the other two enslaved families. Isaac and Susan Hawkins, Thomas and Molly Brown, and Moses and Nancy Queen were forced to commence the difficult work of constructing the novitiate’s new buildings, farming, and sewing, laundering, and cooking for the Jesuits.

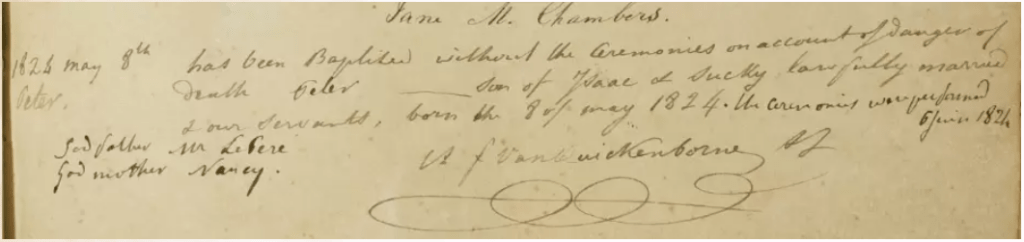

Baptism record for Peter Hawkins, baptized “without ceremonies” on the day of his birth, May 8, 1824, with the ceremonies performed June 6, 1824. Nancy Queen, another woman enslaved to the Jesuits, was his godmother. Image courtesy of the Jesuit Archives and Research Center.

On May 8, 1824, Susan Hawkins gave birth to Peter in their crowded cabin. Peter was baptized conditionally the day of his birth because he was in danger of death. The full ceremonies were performed in June. Records show the family continued to face illness in the coming years. Peter and Susan were often in poor health, and Peter’s brother William, born in April 1834, lived only six months. At age twenty, again in danger of death, Peter received the Catholic sacrament of anointing of the sick.

Through births, purchases, and the transfer of two more families from the White Marsh plantation in Maryland—including some of Peter’s relatives—the enslaved community at Saint Stanislaus grew from seven to about 35 people during Peter Hawkins’ lifetime. After the Jesuits became administrators of Saint Louis College (now Saint Louis University), several of Peter’s kin were sent to labor there. Many enslaved people were transferred back and forth between the Florissant farm at Saint Stanislaus, the downtown university, and the College Farm north of the city over the following years. Peter and his kin-built relationships with and became influential among the enslaved and free African American communities in the Florissant Valley. Enslaved people visited one another across plantations and properties in evening hours. They took advantage of feast days and mass attendance at Saint Ferdinand Church to gather together.

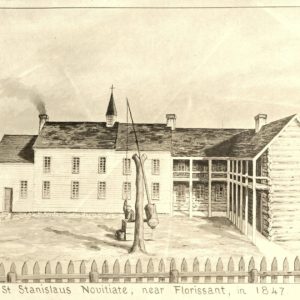

Drawing of the buildings at Saint Stanislaus in 1847. The cabin in the foreground at the left is where Peter Hawkins was likely born, and where his family lived. The white fame building in the center became a chapel for enslaved people two years later, while the smaller frame building attached to it at the right eventually became the laundry. Image courtesy of the Jesuit Archives and Research Center.

Enslaved people at Saint Stanislaus, including Peter Hawkins, sold produce from their own garden plots and worked extra hours at night for pay to obtain funds to make their own purchases or to buy their freedom. Many bondspeople used some of the money to buy better-quality materials than what the Jesuits supplied, so that when they gathered with kin for services, they could show off their finest clothing. People of color gradually began building shanties in the woods near Saint Stanislaus to be nearer to the Jesuits’ enslaved community, and to join them in attending religious services at the chapel later designated on the property for enslaved people.

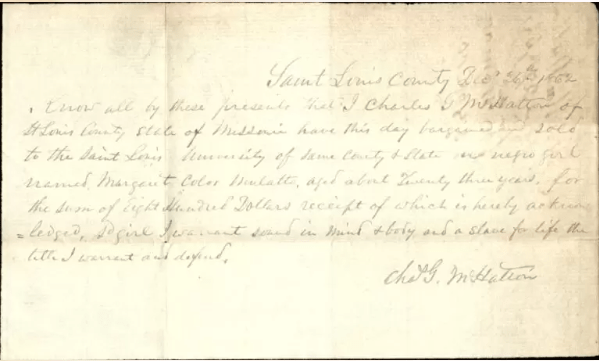

With his kin community, Peter experienced the brutality of enslavement at the hands of his Jesuit masters and participated with fellow bondspeople in resisting their treatment. Peter may have watched as Jesuits prepared to have an enslaved man flogged, until the man’s wife rescued him by throwing herself in front of the whip and flinging her arms around her husband. This couple could have been Peter’s own parents. Peter may have been present on another occasion when enslaved women prevented another person’s beating by picking up rocks to hurl at the inflictor. Peter was only about eight years old when, because a woman refused to remove her own clothing to be whipped, the Jesuit superior ordered a layman to strip and tie her, calling Jesuits to view the whipping as the woman’s sister cried out “My sister is naked!” Peter was also severed from relatives and loved ones when Jesuits sold them away as punishment. Jesuits lauded Peter Hawkins for his religious piety and for being “the best slave,” but Peter’s faith did not stop him from resisting his enslavement to the Jesuits and pursuing freedom. In fact, he leveraged his perceived devotion as a strategy to negotiate with the Jesuits. He arranged with the Jesuits to allow him to work for hire in Florissant and Saint Louis to begin earning money to buy his freedom. Later, in 1862, Peter convinced the Jesuits to purchase a woman named Margaret, whom he wished to marry, from Charles G. McHatton, to prevent them from being separated. Jesuits agreed to this purchase as a supposed “reward” for Peter’s loyalty, but stipulated that Peter, by his own labor, must pay them the $800 price for Margaret’s purchase before the couple could be free.

Bill of sale for the purchase of Peter Hawkins’s wife, Margaret, from Charles G. McHatton, December 26, 1862. Image courtesy of the Jesuit Archives and Research Center.

For two years after marrying Margaret, Peter labored day and night to earn the funds for their freedom. Still, he could not make enough to pay off Margaret’s purchase price —an estimated equivalent of $20,308.04 today— from the meager tips he received from being hired out. In May 1864, Peter came to the Jesuits insisting that the price they were asking him to pay for his and Margaret’s freedom was too much. The Jesuits, in turn, grumbled that Peter must have been prodded on by fellow bondspeople to have become so dissatisfied. Many were already running away or expressing their discontent. Jesuits complained, “Peter, a black slave in our house of Probation [Novitiate], like almost all the other slaves these days, who have gone giddy, wants to leave us and live of his own right. But he had promised to repay us the money that we spent to buy his wife two years ago.” Peter’s persistence forced the Jesuits to compromise. The consultors agreed to absolve half of Margaret’s $800 purchase price. They gave Peter a choice about how he would pay the remaining $400: he and Margaret could either take whatever possessions they had and go live as free people, paying the remainder over time, or Peter could remain laboring for the Jesuits on their property for another two years, after which he and Margaret could then leave as free people without financial obligation. Peter and Margaret chose to stay.

Less than one year into this agreement, Missouri legislators abolished slavery on January 11, 1865. Yet Peter and Margaret continued to labor without compensation for two more years. Several days after the abolition legislation, Missouri Jesuits decided to make contracts “with regard to pay” with all other remaining free people to continue working on the Jesuits’ farm for a salary. However, they held Peter and Margaret in a state of debt peonage (debt slavery), as the couple continued to labor unrecompensed to pay off the imposed debt for Margaret’s purchase. In 1866, Peter requested that the Jesuits grant him a ten-acre plot of farmland on which he could live and work. The Jesuits said no—they claimed it would be inefficient. Peter did not receive a salary until January 15, 1867, two years after the abolition of slavery. Peter’s wages were $14.00 per month; Margaret’s, $5.00 per month. Debt peonage and low wages were just a few of the tactics used by former slaveholders, including the Jesuits, to oppress Black Americans immediately after the abolition of slavery.

Less than one year into this agreement, Missouri legislators abolished slavery on January 11, 1865. Yet Peter and Margaret continued to labor without compensation for two more years. Several days after the abolition legislation, Missouri Jesuits decided to make contracts “with regard to pay” with all other remaining free people to continue working on the Jesuits’ farm for a salary. However, they held Peter and Margaret in a state of debt peonage (debt slavery), as the couple continued to labor unrecompensed to pay off the imposed debt for Margaret’s purchase. In 1866, Peter requested that the Jesuits grant him a ten-acre plot of farmland on which he could live and work. The Jesuits said no—they claimed it would be inefficient. Peter did not receive a salary until January 15, 1867, two years after the abolition of slavery. Peter’s wages were $14.00 per month; Margaret’s, $5.00 per month. Debt peonage and low wages were just a few of the tactics used by former slaveholders, including the Jesuits, to oppress Black Americans immediately after the abolition of slavery.

The 1870 Brick Wall

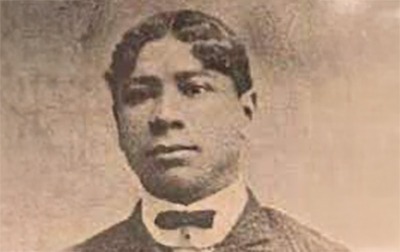

The systematic erasure of enslaved people’s identities prior to 1870, and the lack of historical documentation are obstacles that continue to cause roadblocks for Black Americans seeking to learn about their heritage. These roadblocks are infamously known as the “1870 Brick Wall”.

In 2019, the founders of DSLUE and other Missouri descendants were able to scale over that brick wall when they were contacted by the SHMR Project. In 2021, the project was not disbanded, leaving descendants to their own devices.

Led by a desire to continue to uncover the history of their Ancestors, and to honor them by telling their stories, descendants organized to form the Descendants of the St. Louis University Enslaved, or DSLUE.

Historians Dr. Kelly Schmidt, Ayan Ali, and Cicely Hunter views Henrietta Mills-Chauvin’s application for Charles F. Chauvin’s military pension housed at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Photo courtesy of Kelly Schmidt.

DSLUE descendants standing in front of Dubourg Hall on SLU campus. Founder Bishop Louis William Valentine Dubourg (1766-1883) requested in 1823 that the Maryland Jesuits establish a farm and Novitiate in Florissant and to bring with them “at least four or five or six negroes to prepare and provide additional buildings, and to cultivate the land.”

Aerial sketch of the Jesuit St. Stanislaus Seminary and Farm as it looked in 1836. DSLUE Ancestors helped construct the buildings labeled “Chapel & Refectory under construction” and “Present Rock House.” They lived in the cabin shown to the right.

Why Revealing This History Restores

Bringing together familial ties severed by slavery is beginning to happened as a result of the dissemination of this history. For example, Rashonda Alexander and Alison McCann are cousins who grew up in the St. Louis metro area, not far from Robin Proudie and her family.

Queen Descendant, Alison McCann

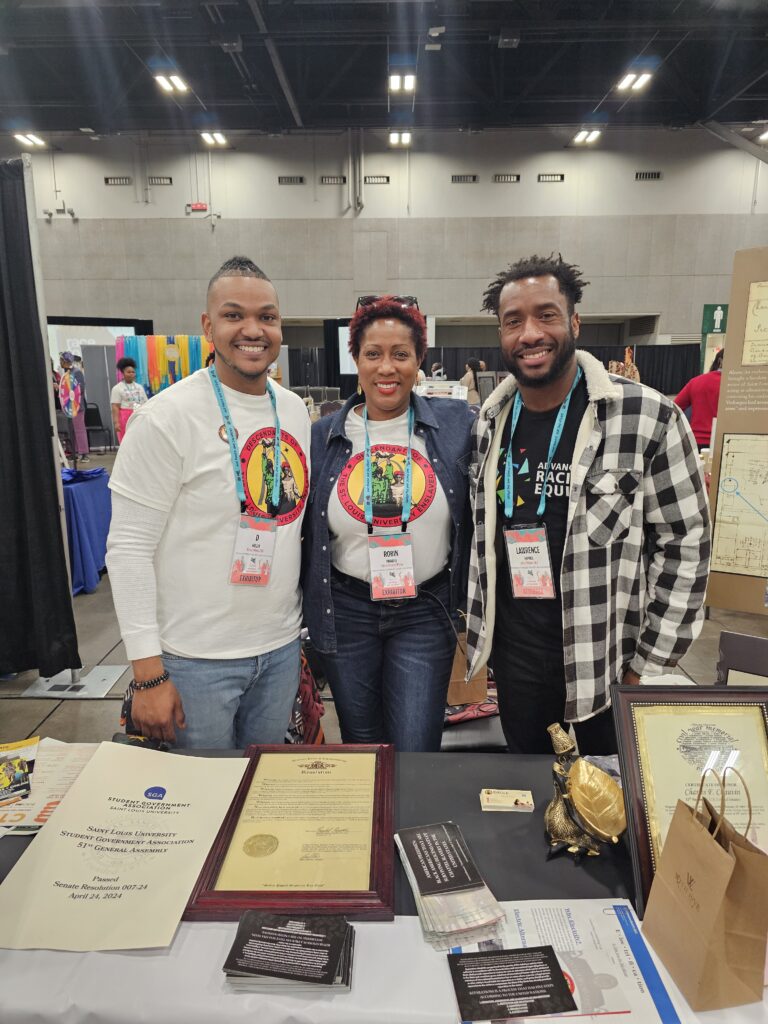

New connections were made when descendants Kevin Porter of Maryland, Robin Proudie and Rashonda Alexander of Missouri discovered their Queen ancestors are related.

It wasn’t until Robin read an article in a St. Louis newspaper that featured Rashonda discussing her connection to this history, that she reached out to Rashonda, then Alison, on social media. Rashonda and Alison are descendants of Jack and Sally Queen, who were cousins to Proteus and Anny- Hawkins Queen.

In 1829, Jack and Sally Queen and their children Notley, Harrison, Augustine, Isaac, Mary, Severine, and Ann, were all forced to Missouri from the Jesuit’s White Marsh plantation in Maryland to labor at the first Jesuit mission in the Midwest, St. Stanislaus, and to sustain St. Louis College, now Saint Louis University.

Henrietta’s mother, Betsy Queen, who was around ten years old, her siblings Ned, Robert, Gabriel, Joseph, Matilda, Mary and her child, and their parents, Proteus, and Anny Hawkins-Queen was also part of that forced migration to Missouri. Peter Queen, who was the son of either Proteus and Anny Hawkins-Queen or of Jack and Sally Queen, was also forced on this journey. The two couples, and their children and grandchild, traversed over 1000 miles down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers to Missouri on a steamboat.

In 1823, Thomas and Molly Brown, Isaac and Susan (Succy) Hawkins, and Moses and Nancy Queen, were the first three enslaved couples forced from White Marsh to help twelve Belgium and French Jesuits expand their presence in the Midwest. They walked from White Marsh to Wheeling, Virginia, then made a harrowing journey along the Ohio River on a flatboat before walking across Illinois and fording the Mississippi River to reach Missouri.

When the Jesuits took over administration of Saint Louis University in 1829, they forced several enslaved people to labor at the college, including Thomas and Molly Brown, Ned Hawkins, and two of Ned’s sisters, whose names were not recorded. Matilda and Betsy Hawkins Queen were later sent to work at the college. Matilda was allowed to marry George Tyler, who was enslaved by Anthony Miltenberger, and Betsy married Abraham Mills, who was also enslaved by a St. Louis family. Both families had children who were born into slavery at Saint Louis University and baptized at Saint Francis Xavier (College) Church.

MATILDA TYLER

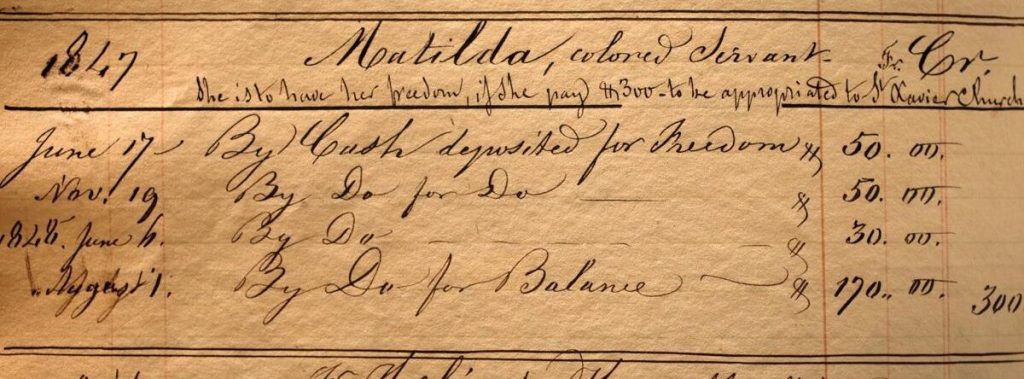

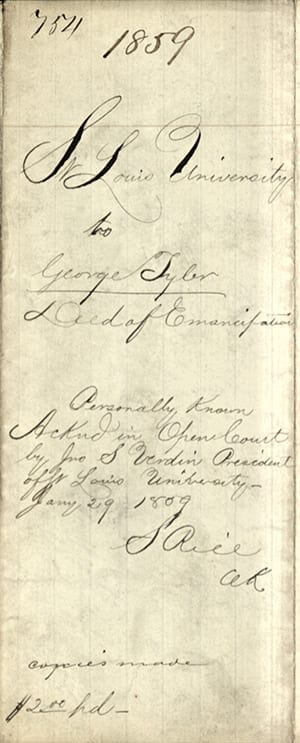

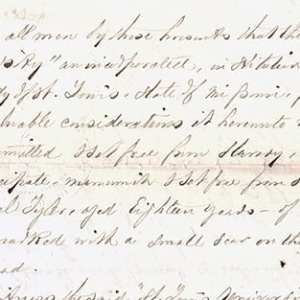

An 1847 entry in the Province Treasury ledgers, under the heading “Matilda, colored servant” reads, “She is to have her freedom, if she pay $300 to be appropriated to St. Fr. Xavier Church.” This is a power example of our Ancestor’s resolve for liberation and freedom. Matilda and George Tyler had six children: Edmond, George, jr., Thomas, Samuel, Joanna, and Anna. Determined to capitalize on Missouri law, which allowed enslaved people to purchase their freedom, Matilda worked tirelessly, laboring during the day for SLU and St. Francis Xavier College Church and hiring herself out at night—paying every cent to then SLU President, Rev. J.S. Verdin, who enslaved her.

By August 1, 1848, after years of relentless labor, she with the help of her recently freed husband, George, Sr., they purchased her freedom and that of their youngest son Charles for $300—equivalent to nearly $9,000 today. But her fight did not stop there. Over the next decade, she worked to free her three surviving sons, a cost of over $20,ooo ttoday, and while mourning the loss of their two daughters, who succumbed to the horrors of enslavement.

SLU’s Board of Trustees minutes confirm that Matilda and her sons received their official emancipation papers in 1859. However, these documents also reveals a painful truth for many institutions still around today: the money Matilda paid for her family’s freedom was appropriated by SLU to fund the expansion of the very institutions that had profited from their enslavement—like the sprawling St. Francis Xavier College that still stands today.

Matilda’s legacy is one of courage, sacrifice, and unrelenting determination. Her youngest son, Charles H. Tyler, became a businessman and political leader in St. Louis, managing one of the first Black baseball teams, the St. Louis Black Stockings, and advocating for Black political representation. Her success is a testament to Matilda’s fight for liberation. Her story is a powerful reminder of the strength of Black resistance in the face of injustice and oppression that we all can call upon today.

DSLUE Ancestor Matilda Tyler’s ledger where it shows payments to the Jesuits for her family’s freedom. She lent herself out from 1847 to 1859 and successfully bought her and her four son’s freedom from the Jesuits at Saint Louis University. Image courtesy of the Jesuit Archives.

DSLUE Ancestor Matilda Tyler’s ledger where it shows payments to the Jesuits for her family’s freedom. She lent herself out from 1847 to 1859 and successfully bought her and her five son’s freedom from the Jesuits at Saint Louis University.

Deed of Emancipation document for Matilda’s youngest son Samuel Tyler which describe him as “copper color and a small scar on his forehead.”

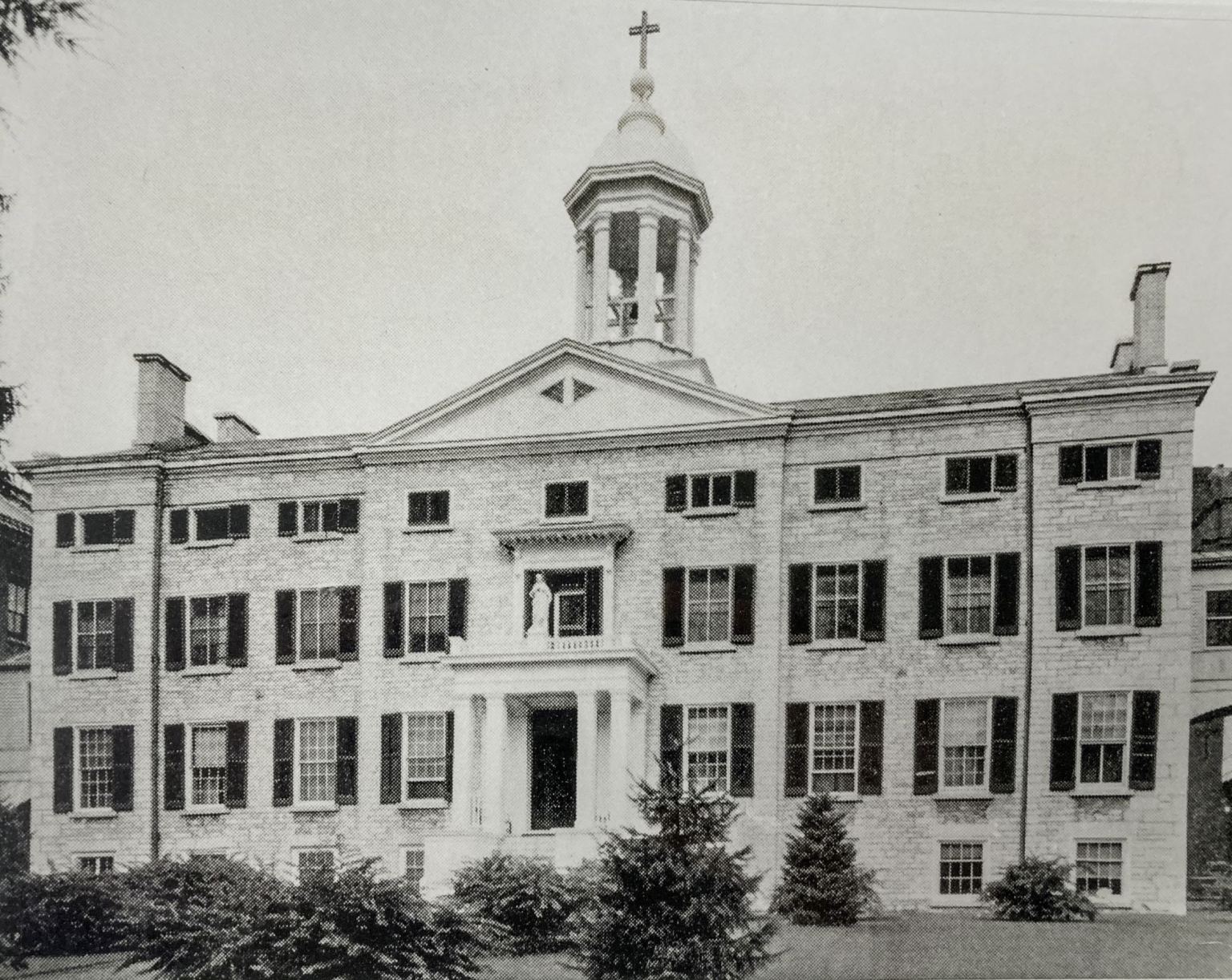

DSLUE ancestors built and sustained St. Stanislaus, the first Jesuit-ran mission located in Florissant, Missouri.

The Rock building built in 1840 by DSLUE enslaved Ancestors. The building is the oldest remaining structure from St. Stanislaus.

Illustration of a Jesuit priest selling an Ancestor’s baby – Copyrighted art by Nanoart.

The Rock Building is now listed in the National Register of Historic Places by the United States Department of Interior.

Descendant Robin Proudie stands at the current St. Francis Xavier College Church. Her enslaved Grandparents, three times removed, Charles Chauvin and Henrietta Mills, were married in the original church in 1860.

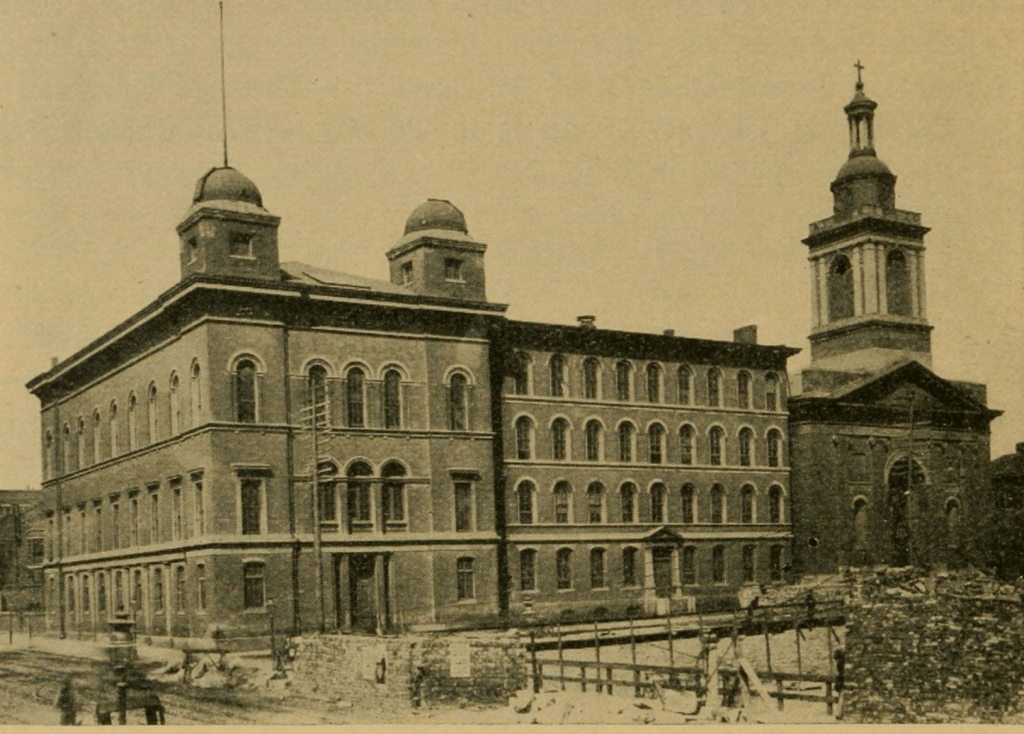

Saint Louis University in 1847.

This image of the ruins of the original St. Francis Xavier (College) Church when it was torn down in the 1880s exposes the segregated chapel designated in 1858 for African Americans, including people enslaved at Saint Louis University. One record describes a boy “of remarkable musical talent” enslaved by the Jesuits, whose name was excluded from the account, who proudly played the chapel’s organ during services.

St. Francis Xavier College Church today

Aerial shot of Saint Louis University 2022.

Descendants’ Sacred Journey of Discovery Brings New Opportunities

With this history being brought out of the darkness and into the light, new discoveries are emerging giving descendants new opportunities for hope and healing.

Descendants are hopeful that during this era of truthtelling by the institutions and corporations that benefitted from centuries of empowing themselves off of the backs of our Ancestors, will move past the platitudes, panel discussions, publications, and press junkets, to truly atone for their past sins. To finally begin to repair historical harms the legacy of chattel slavery, and centuries of anti-black policies that still affect descendant communities to this day.

The linkages across time, spaces, and places crystalizes for descendants the unimaginable reality of the effects of the intergenerational harm done to their bloodlines. Researching and revealing this history is a great first step toward healing and repair, but it’s not the only step.

It is time the Jesuits Central and Southern Province and Saint Louis University live up to it’s core beliefs and commitment to justice. In this instance, it is them who must invoke Examen prayers, and fervently, intentionally, and humbly commit to make up for the injustices they’ve perpetrated against another of God’s children.

We Are One

We strive to unite all descendants of the Jesuit slaveholding diaspora, celebrating our ancestors’ brilliance, bravery, resistance, and perseverance legacy. The original five enslaved couples brought to Missouri from Maryland form the foundation of this shared history, which connects them to descendants of Jesuit-enslaved ancestors sold to Louisiana in 1838 to save Georgetown University, those who remained in Maryland and those trafficked to Kentucky, Kansas City, Kentucky, Alabama, and Louisiana.

We recognize the diversity of thought and experience within descendant communities and encourage all descendants to reclaim, restore, and repair in their own ways. Yet, our shared heritage and commitment to honoring our Ancestors bind us. “We Are One.”

If you have questions or concerns, don’t hesitate to contact us today.

Descendants attend Prayer Ceremony for Jesuit enslaved Ancestor’s abandoned burial grounds at Sacred Heart Church (former land of White Marsh plantation) in Bowie, Maryland.

DSLUE descendants

Descendants of Jesuit enslaved Ancestors from St. Mary’s County, Prince Georges County, Baltimore, Missouri, and Louisiana.

Robin with GU272 Cousins Rochelle and Ruby (Louisiana).

DSLUE, Queen, and Mahoney cousins.

Descendants from Missouri, New Jersey and Delaware

DSLUE descendants in Florida

DSLUE Cousins in St. Louis, Missouri.

DSLUE Cousins in St. Louis, Missouri.

DSLUE Descendants

How We Came to Be

In 2019, the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), a Catholic order of priests, and Saint Louis University (SLU) revealed to us that we are descendants of individuals their predecessors enslaved. These ancestors were forced to labor at the first Jesuit mission in Missouri, St. Stanislaus, Saint Louis University, St. Francis Xavier College Church, and other local churches, farms, and schools from 1823 to 1865.

Historical research uncovered that the Jesuits were active participants and benefactors of slavery from their origins in 1534. To build their wealth, they enslaved thousands globally and trafficked more than 200 Black individuals during their U.S. Midwest and Southern expansion. Many of these individuals are our ancestors.

In 2021, driven by a desire to honor our ancestors and celebrate their resistance and perseverance, we, along with dedicated allies, founded the Descendants of the St. Louis University Enslaved, Inc. In 2023, we officially became a registered 501(c)(3) non-profit organization.

Meet Our Team

Leadership Team

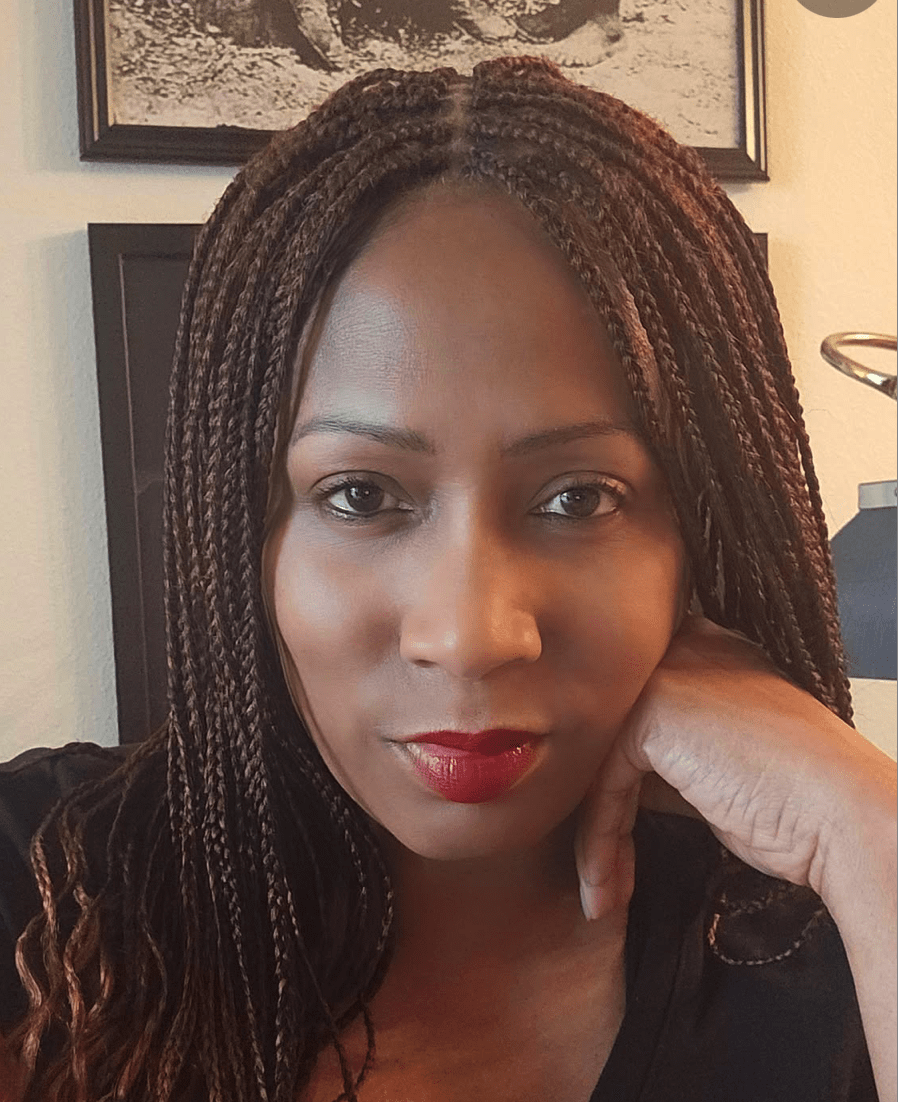

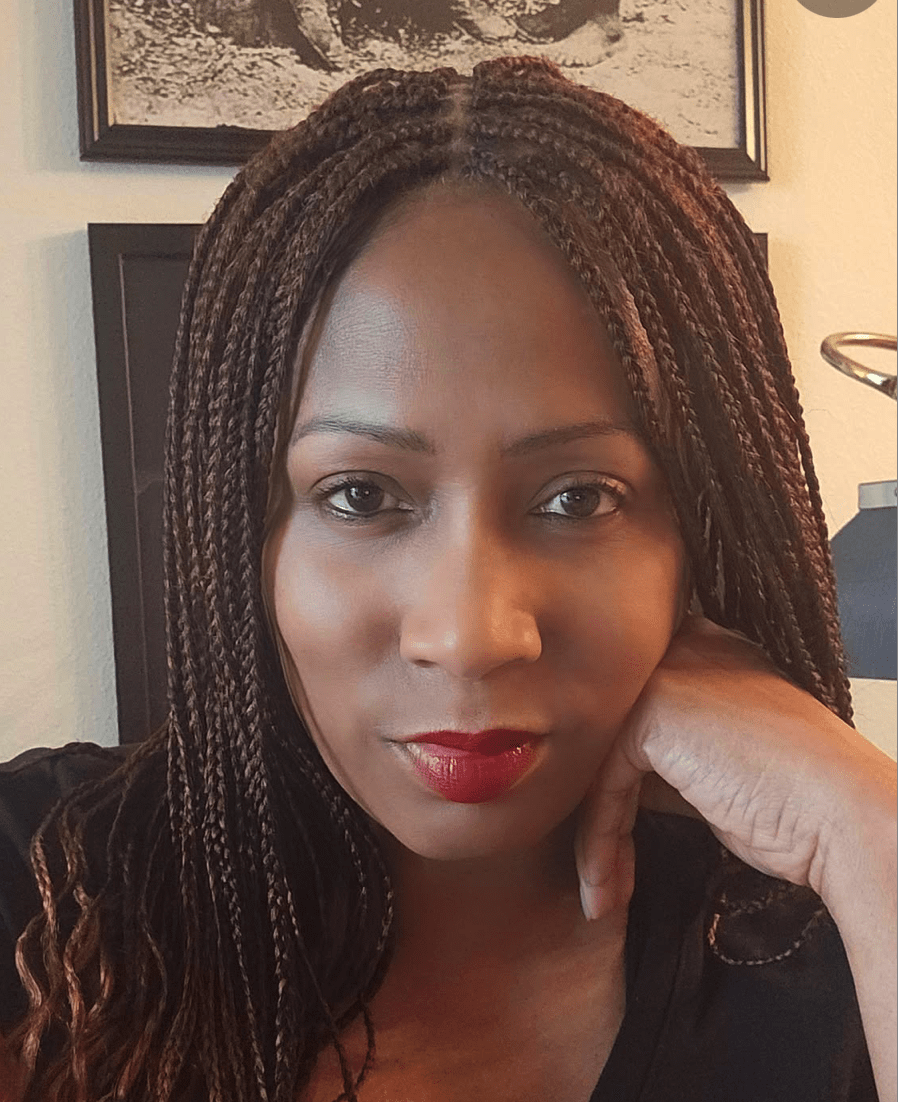

Robin Proudie

Executive Director

DoMarco Holley

Operations Manager, Social Media Manager

Our Board

Robin Proudie

Executive Director

Thurman Stephens, Jr.

President

Claire McFarland, Esq.

Vice President

Lawrence Haynes

Secretary

Staff

Samarya Hall

Student Liaison/Volunteer Coordinator

Dry Bones Get Breath

The founder, Robin Proudie, first learned of her family’s connection to this history when researchers Kelly Schmidt and Ayan Ali presented original documents from the Saint Louis University Archives, Jesuit Archives & Research Center, and other St. Louis, Missouri collections. Among these records was proof that her great-grandmother, three times removed, Henrietta Mills, was born into slavery at Saint Louis University around 1844.

Robin delved into these records, compiled by the Slavery, History, Memory, and Reconciliation (SHMR) Project, which examined the ties of Saint Louis University and the USA Central and Southern Province Jesuits to slavery. This research revealed that over 100 of Robin’s ancestors were trafficked by SLU and the Jesuits in Missouri from 1823 to 1865. For Robin, these documents brought to life the names of ancestors who had been enslaved, silenced, and forgotten.

In late 2019, descendants Safiyah Chauvin, Stephen Chauvin, Greg Holley, and Sonjia Williams joined SHMR working group meetings at Saint Louis University to uncover more about their ancestors’ lives. When the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted in-person gatherings in 2020, Robin adapted to virtual platforms, continuing the vital work started by her elders.

Preserving Our Heritage

One of our most cherished archival records, housed at the Archdiocese of St. Louis Office of Archives and Records, documents the marriage of Charles Chauvin and Henrietta Mills. Written by a Jesuit priest on June 28, 1860, it reads: “I have this day united in the holy bonds of matrimony Charles Chauvin, slave of Mrs. Curtis, and Henrietta Mills, slave of St. Louis University, witnesses Samuel Tyler and Ann Mills.” This union, likely performed in the “colored chapel” of St. Francis Xavier College Church, exemplifies the resilience of our ancestors.

The story of Charles and Henrietta is one of perseverance. Despite the dehumanizing conditions of enslavement, their marriage endured through the American Civil War. In November 1864, Charles was drafted into the U.S. Colored Infantry, where he rose to sergeant. After the war, he returned to St. Louis, reuniting with his wife and children. Together, they built a life of dignity, working as laborers, porters, washers, and carpenters to support their growing family.

A Legacy of Excellence

Between 1860 and 1884, Charles and Henrietta had ten children: Sylvester I, William Francis, Abraham, Peter, Mary Elizabeth, Julia, Rosine, Lincoln, Jerome Alexander, and Louis Ignatius. Lincoln “Link” Chauvin, a direct ancestor of our founders, and his siblings became skilled workers and musicians in St. Louis’s vibrant ragtime scene.

Louis Chauvin, the youngest of the siblings, became the most renowned. A musical prodigy, Louis collaborated with peers like Tom Turpin and Sam Patterson, performing original works and earning acclaim at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. His legacy lives on through compositions such as “The Moon is Shining in the Skies,” “Babe, It’s Too Long Off,” and the celebrated “Heliotrope Bouquet,” co-written with Scott Joplin.

Louis’s brilliance was later immortalized in the 1977 film Scott Joplin, featuring Clifton Davis and Billy D. Williams.

Honoring Our Ancestors

We embrace the truth of our history while celebrating the resilience of our ancestors. Their sacrifices and achievements inspire us to preserve their legacy, repair historical harm, and educate future generations. Through remembrance, restoration, and reparative justice, we honor those who came before us and ensure their stories are never forgotten.

About Descendants of the St. Louis University Enslaved

The lives of those enslaved by the Jesuits and Saint Louis University carry a powerful story of endurance, resistance, and triumph over unimaginable adversity. At Descendants of the St. Louis University Enslaved, we are a non-profit organization dedicated to preserving this history, honoring the resilience of our Ancestors, and advocating for justice in their memory.

Descendants Matter

Breaking Through the 1870 Brick Wall

For Black Americans seeking to trace their ancestry, the lack of historical documentation and the systematic erasure of enslaved people’s identities before 1870 created significant obstacles, often referred to as the “1870 Brick Wall.”

In 2019, founders of the Descendants of the St. Louis University Enslaved and other Missouri descendants overcame this barrier when contacted by the Slavery, History, Memory, and Reconciliation (SHMR) Project. The project connected descendants to their ancestral history through detailed research and archival evidence. However, in 2021, the SHMR Project disbanded, leaving descendants to continue this vital work independently.

Driven to honor their ancestors and uncover their histories, descendants are formally organized as DSLUE, an initiative dedicated to finding, preserving, and sharing the stories of those enslaved by the Jesuits.

Why Revealing Hidden Histories Matter

The uncovering of these histories has begun reuniting familial ties severed by slavery. For example, descendants Rashonda Alexander and Alison McCann grew up near founder Robin Proudie in the St. Louis metro area. Yet, it wasn’t until Robin read an article featuring Rashonda’s connection to this history that she reached out to both Rashonda and Alison. The three discovered they were related through their ancestors, Jack and Sally Queen, cousins to Proteus and Anny Hawkins-Queen (parents of Betsy Queen).

In 1829, Jack and Sally Queen and their children were forced to Missouri from the Jesuits’ White Marsh plantation in Maryland. They labored at the first Jesuit mission in the Midwest, St. Stanislaus, and supported St. Louis College, now Saint Louis University (SLU).

Similarly, Henrietta Mills’ mother, Betsy Queen, and her family endured a forced migration to Missouri along wi. They traversed over 1,000 miles via steamboat on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, while others walked the journey, enduring harrowing conditions.

Enslavement and Resistance

Between 1823 and 1829, the Jesuits brought enslaved people from White Marsh to Missouri to support their expansion. These enslaved individuals included Thomas and Molly Brown, Isaac and Susan Hawkins, and Moses and Nancy Queen, among others. Once in Missouri, they labored to establish Jesuit institutions such as St. Stanislaus and Saint Louis University.

Despite their circumstances, enslaved families like Matilda and Betsy Hawkins (later Mills) sought ways to assert agency. Matilda, for example, labored for over ten years to earn her and her children’s freedom. In 1847, Matilda’s payments to the Jesuits were recorded in ledger entries, culminating in the purchase of freedom for herself and her four sons by 1859. Her perseverance and determination stand as a testament to the resilience of those enslaved.

Documents such as Matilda Tyler’s ledger entries, her son George Tyler’s manumission document, and the deed of emancipation for her youngest son, Samuel Tyler, illustrate the painstaking efforts enslaved individuals made to secure freedom for themselves and their families.

Restoration and Reconciliation

The dissemination of these histories has illuminated the intergenerational harm caused by slavery. Descendants today hope that institutions benefiting from their ancestors’ labor and suffering will take actionable steps beyond acknowledgment—steps toward repairing historical harms and addressing the enduring legacy of systemic inequities.

We emphasize that researching and revealing this history is the first step toward healing and reconciliation. The Jesuits’ Central and Southern Province and Saint Louis University must live up to their stated commitments to justice by taking intentional and meaningful actions to repair past injustices.

A Unified Vision

We strive to unite descendants of the Jesuit slaveholding diaspora, celebrating our ancestors’ brilliance, bravery, resistance, and perseverance legacy. The original five enslaved couples brought to Missouri from Maryland form the foundation of this shared history, which connects them to descendants of Jesuit-enslaved ancestors sold to Louisiana in 1838 to save Georgetown University.

We recognize the diversity of thought and experience within descendant communities and encourage all descendants to reclaim, restore, and repair in their ways. Yet, their shared heritage and commitment to honoring their ancestors bind them. “We Are One.”

If you have questions or concerns, don’t hesitate to contact us today.